Articles

For Kansas National Guard Officers, fates diverge as discipline unfurls

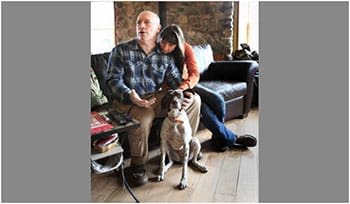

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal) Retired Kansas National Guard Capt. Daniel Beach, with his wife, Becky, and service dog, Sabot, endured a failed attempt by a battalion commander to kick him out of the Army Guard following a deployment to Djibouti in the Horn of Africa.

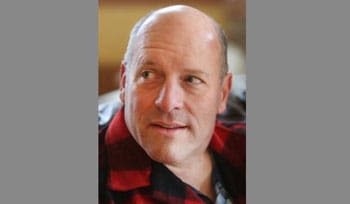

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal) Daniel Beach, who served as a captain in the Kansas National Guard, says U.S. Department of Defense intervention was necessary to force meaningful changes in the dominant leadership culture in the state’s state-led military organization.

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal) Former U.S. Army and Kansas National Guard Capt. Daniel Beach wears a ring commemorating graduation in 1984 from the U.S. Military Academy, but believes some Kansas Guard officers carried a grudge against officers from West Point.

U.S. Navy Kansas National Guard Lt. Col. Greg Mittman, battalion commander, greets newly arriving soldiers of the Kansas Guard’s 2/137th at Djibouti in east Africa in 2010.

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal)

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal)

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal)

(SUBMITTED)

Maj. Gen. Lee Tafanelli the Adjutant General of Kansas speaks before a legislative committee Feb. 2017. (February 2017 File Photo/The Capital-Journal)

Maj. Gen. Lee Tafanelli the Adjutant General of Kansas at a legislative committee Feb. 2017. (February 2017 File Photo/The Capital-Journal)

1981 - Third Class Armor Training (TCAT) at FT Knox, KY - I am in the commander’s cupola of an M60A3.(SUBMITTED)

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal)

(Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal)

Capt. Daniel Beach can follow the demise of his military career like a tracer round to a pair of menacing decisions by commanders in the Kansas National Guard.

A close examination of inventory documents in 2009 revealed more than 50 bayonets, several close-combat gun sights, and some night-vision goggles were found to be missing from the National Guard armory in Kansas City, Kan. Instead of focusing on the recovery of AWOL war-fighting gear, Beach said, he was pressured to sign falsified documents attesting to a clean-count inventory and instructed not to conduct an inquiry into the thefts.

Two enlisted men were eventually implicated in the crime, but Beach said a man who went on to become a two-star general and Kansas’ adjutant general, Lee Tafanelli, brought a hammer down on him for failing to shield others who could be embarrassed by the heist. Beach said he tried to explain how he was boxed in.

RELATED: Internal investigation of Kansas Guard pinpoints ‘toxic’ leadership

"He cut me off," Beach said. "He chewed my butt off for how irresponsible I had been because I wouldn’t take the hit for everybody. Just ripped me. I’m not a ‘team player’ because I didn’t cover it up."

Beach said he again experienced good-ol’-boy etiquette amid preparations for deployment to the Horn of Africa with a battalion commander, Lt. Col. Gregory Mittman, who demanded loyalty from junior officers. When it became evident Beach wouldn’t be adequately pliable, Mittman dedicated himself to building a case for kicking the captain out of the Kansas Guard. After returning from Africa, following 18 months of delays, Mittman brought formal charges.

"In my personal opinion and professional opinion, I think he failed to do his duty," Mittman said while testifying at Beach’s ouster hearing in Topeka. "He has a problem with judgment and I don’t believe that he was very loyal to his organization."

Other testimony in the case against Beach, which he survived, appeared to substantiate claims the captain was singled out for punishment by Mittman.

The career intersection of Beach and Mittman — both men landed in hot water halfway around the world, but experienced a different fate back home — helped expose a secretive side of the Kansas Guard.

"If it relates to investigations or personnel actions, I’m just not going to go down that road and discuss it," Tafanelli said during a brief conversation at the Capitol.

The Mittman-Beach dynamic touched threads of a story published by The Topeka Capital-Journal in January based on evidence that members of the Kansas Guard engaged in enlistment fraud, racism, sexual assaults, impermissible fraternization, manipulation of promotions, retaliation against troops and subterfuge of internal investigations.

Kansas Guard officers who conducted that investigation urged Tafanelli to confront "toxic" leadership, but the adjutant general pushed back on behalf of the organization he had led for six years since being appointed by Gov. Sam Brownback.

Tafanelli pledged to share evidence proving the Kansas Guard acted appropriately, but he instead asked the National Guard Bureau in Washington, D.C., to review the state’s handling of alleged misconduct. A Kansas Guard official said initial feedback from the ongoing external assessment was "positive," but noted an exemption in the Freedom of Information Act as justification for not commenting publicly about personnel matters.

On Tuesday, the Kansas Guard made available Brig. Gen. Anthony Mohatt, commander of the Kansas Army Guard, to answer broad questions about the administration of justice in the organization but not to speak about specific incidents or individuals. He said the Kansas Guard was part of the "world’s premier fighting force" that couldn’t effectively deploy overseas or respond to natural disasters in Kansas if poorly led.

"We follow the Army values. We’re proud of it," said Mohatt, who acknowledged some individuals engage in misconduct. "I want to make sure it’s known that you’re dealing with a very small number that belongs to that category. They get their due process and, ultimately, the decisions are made."

Marked for death

During a Kansas Guard deployment to the Republic of Djibouti in 2010 and 2011, Beach and Mittman found multiple points of conflict.

Mittman was commanding officer of Beach and 500 other soldiers in Kansas’ 2nd Combined Arms Battalion, 137th Infantry Regiment. They were sent to the Islamic country adjacent to strategic shipping lanes and within drone range of hostilities. Beach’s role in the 2/137th was to supervise security at Camp Lemonnier’s front gate and, later, to serve in the battalion’s command operations center.

Mittman testified the battalion’s overall morale suffered when boots hit the ground in Djibouti. He said soldiers from Kansas wanted to chase an enemy rather than pull guard duty on an austere base in a scorching land bordered by Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and the Red Sea.

"They were doing a mission that many of them felt was beneath them," he said. "I would say that their morale was lower than it had been when we were stateside."

Mittman said his working relationship with Beach deteriorated to the point he was convinced Beach’s flaws made him a burden to any commander at any level. He initiated the quasi-legal process to strip Beach of his federal authorization to serve in the Kansas Guard.

Officers on the military review board that conducted the 2012 inquiry didn’t find sufficient evidence to accept Mittman’s script for driving him out. Hundreds of pages of documents tied to the case did raise questions about whether the Kansas Guard tried to distort justice.

One of Beach’s defense attorneys, former U.S. Army Reserve officer Joseph DeWoskin, said the charges against Beach reflected a personal vendetta. The protagonists were Mittman and two subordinates — Maj. Kevin Braun and Capt. Brent Buckley.

"Lt. Col. Mittman and, meaning no disrespect, but I’m going to say it anyway, and his two minions, did what they could to attack this officer and kick him the heck out of this Army," DeWoskin said. "Beyond these three officers, the government was unable to produce one soldier, one other officer, who could come in and say that Captain Beach was a terrible commander, was a terrible officer, did something illegal, immoral or otherwise."

Beach, who had a 14-year break between U.S. Army service and appointment to the Kansas Guard, admitted his military demeanor created friction within a cliquish Kansas Guard culture that knew how to play favorites. He also detected animus among some in the Kansas Guard toward those who, like himself, were graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y.

"By showing up and doing my job, I totally upset their apple cart," said Beach, who teaches at a parochial school in northwest Missouri. "That marked me for death. The other thing was, I hadn’t made any bones by hiding things. If you don’t play and cover up the skeletons, they’ll get you."

Armenian connection

One of those skeletons in the closet related to whether Mittman was shielded from proportionate scrutiny amid allegations of unprofessional conduct in 2012 while on assignment in Armenia. Mittman had been dispatched to serve as an adviser to soldiers preparing for a NATO peacekeeping assignment and to build upon an alliance forged in 2003 between Kansas and Armenia.

Five current and former Kansas Guard members said Mittman triggered scandal by getting drunk at a diplomatic event in Armenia. Mittman shouted "bitch" at a female Kansas Guard officer, the sources said. Mittman was allegedly escorted from the venue by colleagues from Kansas. After stopping at a store, sources said, Mittman asked a boy on the street how much it would cost to buy his sister.

Within hours, Mittman was on a plane streaking back to Kansas.

The former and current Kansas Guard members said Mittman was placed on a glide path to retirement without exposure to the level of scrutiny he compelled Beach to endure. Mittman left the Kansas Guard in mid-2013 and still works as principal of Valley Center Middle School.

"I regret some of my actions in 2012 while serving in Armenia and that those actions offended those with which I served," Mittman said in a statement Tuesday. "I alone am responsible and any connection between my actions and former leadership would be inappropriate."

Retired Kansas Guard Col. Michael Dittamo, who served 34 months as a deployed commander, said Beach possessed requisite skills to be an Army officer. Dittamo, called as a defense witness for Beach, said he wasn’t sure Mittman fully dedicated himself to soldiers.

"That doesn’t mean he loves them to the extent that he babies them and they can’t do their mission, because you’ve got to get the mission done," Dittamo said. "But does he really, genuinely give a damn? I don’t know if Mittman does or not."

During the Horn of Africa deployment, Mittman gave Beach an unsatisfactory job performance review, which Beach asserted contained misleading information. Mittman blamed Beach for granting approval for a civilian contractor to be strip-searched at the camp’s entrance after security monitors detected the possibility of something hidden near the man’s groin.

However, Daniel Mitchell, who was a sergeant deployed with the 2/137th in Djibouti, said he authorized the search.

"It was my call, and I believe I did the right thing," Mitchell said. "If we would have found a bomb, we would have been heroes."

Alarms sounded again when Mittman accused Beach of permitting a sergeant to improperly work back-channel connections in Kansas to secure overdue promotions and proper pay raises for two dozen enlisted personnel serving in Djibouti.

Jeffrey Beam, a sergeant first class assigned to Beach, said the battalion fumbled promotion orders for months so he "ran pretty autonomously" to complete the promotions, which were later rescinded and then affirmed.

The bullet

It was an intense exchange between Mittman and Beach while the battalion was transitioning home through Fort McCoy, Wis., that fully exposed the end game. Beach was called on the carpet for having in his possession a solitary 5.56 mm cartridge. Beach told Mittman the M-4 cartridge was part of an investigation of a firearm incident involving one of the state’s enlisted soldiers. Beach said U.S. Navy personnel in charge of the East Africa base signed out the bullet so he could maintain chain of custody.

"I said, ‘You’re some piece of work, Beach,’ " Mittman recalled during testimony at Beach’s disciplinary hearing. "At some point, I believe, I said, ‘Why don’t you just (obscenity) go away?’ "

Beach wasn’t about to quit, but at that moment on the post in western Wisconsin, he asked Mittman three times to take a break. Mittman ignited, so Beach exited the room with Mittman still talking. Beach promised to return when Mittman regained composure. Mittman called Beach’s conduct "gross insubordination."

"I said, ‘Beach, get back here before me. You’ll stand at attention. Beach, you’re disobeying a direct order. Get back here,’ " Mittman said, according to a transcript of the tribunal. "I lost my temper. I let him know that I was very upset with him."

Beach’s defiance of that stand-at-attention order and alleged mishandling of the munition were among issues raised by Kansas Guard prosecutors to justify filing a case to withdraw Beach’s federal authority to serve as an officer. Mittman’s case against Beach also featured charges of moral and professional dereliction, failure to exercise leadership, inability to appropriately carry out assignments, display of a defective attitude, inappropriate field promotions and conveying to enlisted personnel that an officer was a liar.

The prosecutor who handled the case, Kansas Guard officer Jeremy Hart, said the decision to proceed wasn’t reached wantonly.

"All deployments are tough, and I imagine that this deployment’s no different," Hart said. "I understand, however, that officers should not be insubordinate in carrying out their mission. Being a good soldier is not enough."

Beach, who held the burden of proof during this tribunal, was found by a panel of senior officers to have engaged in unprofessional conduct by ignoring Mittman’s order to stand at attention, but that act "did not warrant withdrawal of federal recognition." Beach said a couple of members of the military board afterward shook his hand and advised him not to anger lieutenant colonels.

DeWoskin, one of Beach’s defense lawyers, said Mittman marked Beach for failure during pre-deployment drills in Salina and Fort Lewis, Wash., and pressed the case while stationed in Djibouti.

"They put him into a position whereby he had no hope of success. A toxic environment is what was going on in this unit in Djibouti," DeWoskin said.

Evidence emerged at Beach’s hearing that Mittman advised his subordinates not to provide required mentor counseling to Beach. An enlisted soldier, Michael Leo, testified Buckley pressured him to sign a sworn statement about Beach.

"He tried to coerce me to make a statement," said Leo, a now-retired sergeant who deployed to the Horn of Africa with the 2/137th.

DeWoskin said a written evaluation of Beach’s performance contained nearly identical language from Buckley and Maj. Richard Eaton.

"If you’re trying to infer," Mittman said, "that I influenced Capt. Buckley to go with Maj. Eaton’s rating, I can tell you unequivocally I did not do that. In fact, I specifically told Capt. Buckley, ‘I’m not putting pressure on you.’ "

"It’s almost verbatim," DeWoskin replied.

"People have a tendency to use the same verbiage if the situation fits," Mittman said. Radioactive Beach said he reluctantly agreed not to take the stand on the advice of legal counsel, but about a dozen people testified on his behalf. Members of the military panel — Col. Dino Sarracino, Lt. Col. Erich Campbell, Maj. Damon Frizzel and Lt. Col. Roger Aeschliman — had plenty of questions for witnesses.

Sarracino, the president of the panel, pushed Buckley to explain why he orally characterized Beach’s performance in Africa as compared to peers but recommended in writing against promoting Beach.

"Capt. Buckley, did somebody tell you to put that or did you do that of your own volition?"

"I did that on my own," Buckley said.

Picking up that thread, Campbell asked Buckley whether Mittman set out to destroy Beach’s career.

"I don’t think he was out to get him," said Buckley, a former El Dorado police officer. "Could it be perceived that he was out to get him?" Campbell asked.

"Yes," Buckley said.

In the end, Beach said, he may have won a battle against Mittman, but he lost the broader conflict that prematurely ended his career in uniform.

Beach, who graduated from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, applied for a full-time Kansas Guard job, but was informed leadership considered him "radioactive." He was passed over for promotion a couple of times. He retired in 2015, partly because of medical complications, with 21 years of service.

He said the U.S. Department of Defense ought to stabilize the Kansas Guard with an infusion of consistent, honest leadership at the top. He was skeptical such a silver bullet would hit the mark in Kansas.

"Big Army needs to come in and clean house," Beach said. "Until you get a true leader rather than a political powermonger into the seat, it won’t change. No one is protecting the soldiers. That is what is important to me."

On the Kansas National Guard: 5 Things You Need to Know

Daniel Beach, who served as a captain in the Kansas National Guard, says the U.S. Department of Defense intervention was necessary to force meaningful changes in the dominant leadership culture in the state’s state-led military organization. (Thad Allton/The Capital-Journal) The Kansas National Guard’s handling of disciplinary cases raises questions of transparency and fairness. Here are 5 things you need to know:

Kansas National Guard Capt. Daniel Beach was accused of insubordination by Lt. Col. Gregory Mittman after deploying to East Africa. In 2012, an officer review panel ruled facts didn’t support Mittman’s bid to kick Beach out of the Guard.

Questions linger about the Kansas Guard’s handling of subsequent allegations Mittman became intoxicated at a diplomatic event in Armenia, called a female Kansas officer a "bitch" and drunkenly asked the cost of buying a young girl. Mittman apologized for his conduct.

Joseph DeWoskin, an attorney for Beach, said Mittman created a "toxic" environment for Beach’s unit in the Horn of Africa and pursued a personal vendetta against the West Point graduate.

Kansas Guard prosecuting attorney Jeremy Hart said the decision to seek dismissal of Beach wasn’t made lightly and "being a good soldier" didn’t offset an officer’s repeated insubordination.

Brig. Gen. Anthony Mohatt, commander of the Kansas Army Guard, said "we follow Army values" and the military organization couldn’t effectively respond to a natural disaster in Kansas or deploy as a fighting force if poorly led.

Keep reading: For Kansas National Guard officers, fates diverge as discipline unfurls